The ritual bronzes of the early Western Zhou continued the late Anyang (安陽) tradition; many were made by the same craftsmen and by their descendants. Even in the predynastic Zhou period, however, new creatures had appeared on the bronzes, notably a flamboyant long-tailed bird that may have had totemic meaning for the Zhou rulers, and flanges had begun to be large and spiky. By the end of the 9th century BC, moreover, certain Shang shapes such as the gu (觚) and gong (觥) were no longer being made, and the taotie (饕餮) and other Shang zoomorphs had been broken up and then dissolved into volutes or undulating meander patterns encircling the entire vessel, with little apparent symbolic intent.

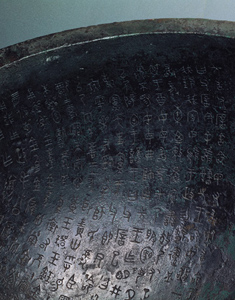

From the outset of Zhou rule, vessels increasingly came to serve as vehicles for inscriptions that were cast to record events and report them to ancestral spirits. An outstanding example, excavated near Xi’an in 1976, was dedicated by a Zhou official who apparently had divined the date for the successful assault upon the Shang and later used his reward money to have the bronze vessel cast. By late Zhou times a long inscription might have well over 400 characters. The longest discovered so far is on the Cauldron of Duke Mao (毛公鼎), which has 499 characters.

The bronzes of the Eastern Zhou period, after 771 BC, show signs of a gradual renaissance in the craft and much regional variation, which appears ever more complex as more Eastern Zhou sites are unearthed. Often adorned with boldly modeled handles in the form of animal heads, 8th- and 7th-century BC bronzes are crude and vigorous in shape. Typical vessels of this phase have been found in a cemetery of the small feudal state of Guo (虢) in Henan province. Vessels from Xinzheng (新鄭) in Henan (8th–6th century BC) reveal a further change to more elegant forms, often decorated with an allover pattern of tightly interlaced serpents; the vessel may be set about with tigers and dragons modeled in the round and topped with a flaring, petaled lid.

The aesthetic tendency toward elaboration was given further stimulus by the introduction of the lost-wax method (失蠟法) of production (by the late 7th century BC), leading quickly to zealous experiments in openwork design that are impressive technically though often heavy in appearance and gaudy in effect. The style of bronzes found at Liyu (李峪) in Shanxi (c. 6th–5th century BC) is much simpler, more compact, and unified; the interlaced and spiral decoration is flush with the surface. Thereafter, until the end of the dynasty, the bronze style became increasingly refined: the decoration was confined within a simpler contour, and the interlacing of the Xinzheng style gave way to the fine, hooked “comma pattern” of the vessels of the 5th and 4th centuries BC. By this time, bronze decor had come under the influence of textile patterns and technique, particularly embroidery, as well as of lacquer decor, suggesting the bronze medium’s decline from primacy. Bronzes decorated in this manner have been found chiefly in the Huai River valley.

In the Zhou Dynasty, bronze bells emerged. Perhaps the oldest class is a small clappered bell called ling (鈴), but the best known is certainly the zhong (鐘), a suspended, clapperless bell. Zhong were cast in sets of eight or more to form a musical scale, and they were probably played in the company of string and wind instruments. The section is a flattened ellipse, and on each side of the body appear 18 blunt spikes, or basses, arranged in three double rows of three. These often show marks of filing, and it has been suggested that they were devices whereby the bell could be tuned to the requisite pitch by removing small quantities of the metal. The oldest specimen recovered in a closed excavation is one from Pudu Cun, dating from the 9th century BC.

The finest example discovered so far is an orchestral set of 64 bells, probably produced in Chu (楚) and unearthed in 1978 from a royal tomb of the Zeng (曾) state, at Leigudun (擂鼓墩) near Sui Xian (隨縣) in Hubei Province. The bells were mounted on wooden racks supported by bronze human figurines. They are graded in size (from about 20 to 150 cm [8 to 60 inches] in height) and tone (covering five octaves), and each is capable of producing two unrelated tones according to where it is struck. Gold-inlaid inscriptions on each bell present valuable information regarding early musical terms and performance, while a 65th bell with flat bottom called bo (镈) is dedicated by inscription from the king of Chu to Marquis Yi of Zeng (Zeng Hou Yi, 曾侯乙), the deceased, and bears a date equivalent to 433 BC.

Bronze mirrors were also used in the Zhou Dynasty, not only for toiletry but also as funerary objects, in accordance with the belief that a mirror was itself a source of light and could illuminate the eternal darkness of the tomb. A mirror also was thought of as a symbolic aid to self-knowledge. Ancient Chinese mirrors were generally bronze disks polished on the face and decorated on the back, with a central loop handle or pierced boss to hold a tassel. The early ones were small and worn at the girdle; later they became larger and were often set on a stand. Mirrors, however, were not widely used until the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. The present day Changsha of Hunan Province, which was in the state of Chu, was a center for the manufacture of late Zhou mirrors, the designs on which consist chiefly of zigzag lozenges, quatrefoil petals, scallops, a hooked symbol resembling the character for “mountain” (shan, 山), and sometimes animal figures superimposed on a dense allover pattern of hooks and volutes. These mirrors are often thin, and the execution is refined and elegant.