The human figure as a subject in Chinese painting appeared well before such later popular ones as the landscape or birds-and-flowers. The purpose behind the painting of figures in early times was mostly to serve religious or political aims. Archaeological discoveries of paintings on silk and on tomb and cave walls so far offer a glimpse at the development of figure painting from the Spring and Autumn (722-481 BC) to Warring States (403-221 BC) periods, to the Han dynasty (206 BC - AD 220), and into the Wei and Jin era (265-420).

After the Han dynasty, the breakdown of the Confucian system was reflected in painting and painting theory: increasingly, Daoist and Buddhist themes and theoretical reasons for painting were emphasized. The greatest painter in the Jin dynasty was Gu Kaizhi (顧愷之, ca.344-406), an amateur painter from a family of distinguished Eastern Wei dynasty scholar-officials in Nanjing and an eccentric member of a Daoist sect. One of the most famous of his works (which survives in a Tang dynasty copy in the British Museum) illustrates a 3rd-century didactic text Nüshizhen (女史箴, “Admonitions of the Court Instructress”), by Zhang Hua (張華, ca.232-300). The figures are slender and fairylike, and the line is fine and flows rhythmically. The roots of this elegant southern style, which then epitomized the highest Nanjing court standard, can be traced back to Changsha in the late Zhou (1046–256 BC)–early Han period, and it was later adopted as court style by the Northern Wei rulers (e.g., at Longmen) when they moved south to Luoyang in 495. Gu Kaizhi also was noted as a portraitist, and, among Buddhist subjects, his rendering of the sage Vimalakirti became a model for later painters.

Into the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-589), the south saw few major painters in the 5th century, but the settled reign of Wudi (武帝) in the 6th produced a number of notable figures, among them Zhang Sengyao (張僧繇, fl. ca.490-540), who was commissioned by the pious emperor to decorate the walls of Buddhist temples in Nanjing. All his work is lost, but his style, from early accounts and later copies, seems to have combined realism with a new freedom in the use of the brush, employing dots and dashing strokes very different from the fine precision of Gu Kaizhi.

Painters in northern China were chiefly occupied in Buddhist fresco painting (painting on a freshly plastered wall). While all the temples of the period have been destroyed, a quantity of wall painting survives at Dunhuang (敦煌) in northwestern Gansu in the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, Qianfodong (千佛洞), where there are nearly 500 cave shrines and niches dating from the 5th century onward. Early Dunhuang paintings chiefly depict incidents in the life of the Buddha, the Jatakas (stories of his previous incarnations), and such simple themes as the perils from which Avalokiteshvara (Chinese Guanyin) saves the faithful. In style they show a blend of Central Asian and Chinese techniques that reflects the mixed population of northern China at this time.

The patronage of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) courts attracted painters from all over the empire. Yan Liben (閻立本, ca.601-673), who rose to high office as an administrator, finally becoming a minister of state, was also a noted 7th-century figure painter. His duties included painting historical scrolls, notable events past and present, and portraits, including those of foreigners and strange creatures brought to court as tribute, to the delight of his patron, Taizong (太宗). Yan Liben painted in a conservative style with a delicate, scarcely modulated line. Part of a scroll depicting 13 emperors from Han to Sui is attributed to him. Features of his style may possibly be preserved in wall paintings in 7th- and early 8th-century tombs in northern China, notably that of Princess Yongtai (永泰公主, 685-701) near Xi’an.

The royal tombs near Xi’an show the emergence of a more liberated tradition in brushwork that came to the fore in mid- to late 8th-century painting, as it did in the calligraphy of Zhang Xu (張旭, fl. 8th c.), Yan Zhenqing (顏真卿, 709-785), and other master writers. The greatest brush master of Tang painting was the 8th-century artist Wu Daozi (吳道子, ca.680-759), who not only enjoyed a career at court but had sufficient creative energy to execute, according to Tang records, some 300 wall paintings in the temples of Luoyang and Chang’an (modern Xi’an). His brushwork, in contrast to that of Yan Liben, was full of such sweeping power that crowds would gather to watch him as he worked. He painted chiefly in ink, leaving the coloring to his assistants, and he was famous for the three-dimensional, sculptural effect he achieved with the ink line alone. Wu Daozi had a profound influence, particularly on figure painting, in the Tang and Song dynasties. His style may be reflected in some of the 8th-century caves at Dunhuang, although the meticulous handling of the great paradise compositions in the caves increasingly came to approximate the high standards of Chinese court artists and suggests the inspiration of earlier and more conservative Buddhist painters. This more restrained style can also be seen in the Japanese temple murals at Hōryū Temple near Nara, executed about 670–710 in the Chinese “international” manner.

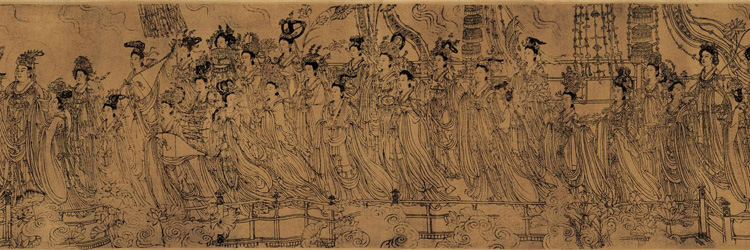

Figure painters who depicted court life in a careful manner derived from Yan Liben rather than from Wu Daozi included Zhang Xuan (張萱, 713-755) and Zhou Fang (周昉, ca.730-800). The former’s Court Ladies Preparing Silk (搗練圖) survives in a Song dynasty copy by Huizong (徽宗), while later versions of several compositions attributed to Zhou Fang exist. Eighth-century royal tomb murals and Dunhuang Buddhist paintings demonstrate the early appearance and widespread appeal of styles that these court artists helped later to canonize, with individual figures (especially women) of monumental, sculpturesque proportion arranged upon a blank background with classic simplicity and balance.

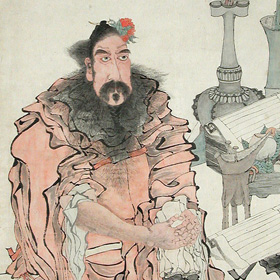

In the middle to late Tang, more adventurous brush technique was developed by such painters as Wang Qia (王洽, also known as Wang Mo 王墨) and Gu Kuang (顧況), southern Chinese Daoists who “splashed ink”. The intention of these ink-splashers was philosophical and religious as well as artistic: it was written at the time that their spontaneous process was designed to imitate the divine process of creation. Their semifinished products, in which the artistic process was fully revealed and the subject matter had to be discerned by the viewer, suggested a Daoist philosophical skepticism. These techniques marked the emergence of a trend toward eccentricity in brushwork that had free rein in periods of political and social chaos. They were subsequently employed by painters of the southern “Sudden” school of Chan (Zen) Buddhism, which held that enlightenment was a spontaneous, irrational experience that could be suggested in painting only by a comparable spontaneity in the brushwork. Chan painting flourished particularly in Chengdu, the capital of the petty state of Shu, to which many artists went as refugees from the chaotic north in the last years before the Tang dynasty fell. Among them was Guanxiu (貫休), an eccentric who painted Buddhist saints with a weird air and exaggerated features that had a strong appeal to members of the Chan sect. The element of the deliberately grotesque in Guanxiu’s art was further developed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960) by Shi Ke (石恪), who was active in Chengdu in the mid-10th century. In his paintings, chiefly of Buddhist and Daoist subjects, he set out in the Chan manner to shock the viewer by distortion and roughness of execution.

The southern court painters, notably Gu Hongzhong (顧閎中, ca.910-980) and Zhou Wenju (周文矩, 10th c.), depicted the voluptuous, sensual court life under Li Houzhu. A remarkable work attributed to Gu Hongzhong depicts the scandalous revelries of the minister Han Xizai. Zhou Wenju was famous for his pictures of court ladies and musical entertainments, executed with a fine line and soft, glowing color in the tradition of Zhang Xuan and Zhou Fang.

In the Northern Song (960-1127), the last great exponent of the Tang figure-painting tradition was Li Gonglin (李公麟, 1049-1106). In early life Li was a famous painter of horses until, so the story goes, a Daoist told him that if he continued much longer in this vein he would become like a horse himself, whereupon he switched to other themes. He was thoroughly eclectic, spending years copying the old masters, and excelled in ink line (白描) painting, without color, shading, or wash. Li Gonglin brought a scholar’s refinement of taste to a tradition theretofore dominated by Wu Daozi’s dramatic style, and provided a model for figure painters that endured down to Ming times.

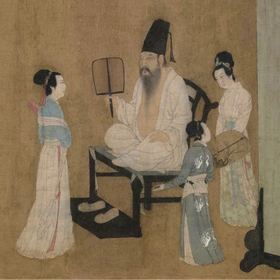

The last emperor of the Northern Song is Huizong (徽宗), who sought escape from affairs of state through the pleasures of arts and letters. He urged painters in his academy of painting to depict objects that were “true to color and form,” inviting an extreme literalness of representation. Huizong was also a player of the traditional string instrument, qin (琴), as exemplified by his famous painting “Listening to the Qin (聽琴圖).”

In the first two generations of the Southern Song (1127-1279), however, historical figure painting regained its earlier dominance at court. Gaozong (高宗) and Xiaozong (孝宗), respectively the son and grandson of the imprisoned Huizong (徽宗), sought to legitimize their necessary but technically unlawful assumption of power by supporting works illustrating the ancient classics and traditional virtues. Such works, by artists including Li Tang (李唐, ca.1050-1130) and Ma Hezhi (马和之, 12th c.), often include lengthy inscriptions purportedly executed by the emperors themselves. They represent the finest survival today of the ancient court tradition of propagandistic historical narrative painting in a Confucian political mode.

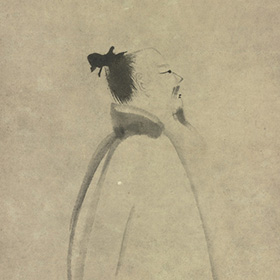

Toward the end of this period, Chan (Zen) Buddhist painting experienced a brief but remarkable florescence, stimulated by scholars abandoning the decaying political environment of the Southern Song court for the monastic life practiced in the hill temples across the lake from Hangzhou. The court painter Liang Kai (梁楷, ca.1140-1210) had been awarded the highest order, the Golden Girdle, between 1201 and 1204, but he put it aside, quit the court, and became a Chan recluse. What is thought to be his earlier work has the professional skill expected of a colleague of Ma Yuan (馬遠, ca.1160-1225), but his later paintings became freer and more spontaneous. Chinese connoisseurs disapproved of the rough brushwork in Chan paintings. However, his work, and that of other Chan artists such as Muqi (Muxi, 牧谿), was collected and widely copied in Japan, forming the basis of the Japanese suiboku-ga (sumi-e) tradition.

In the Yuan period (1271-1368), when the ruling Mongols curtailed the employment of Chinese scholar-officials, the theme of the groom and horse – one associated with the legendary figure of Bole (伯樂), whose ability to judge horses had become a metaphor for the recruitment of able government officials – became a symbolic plea for the proper use of scholarly talent. Other figure paintings of this period often served as a reference to the past, such as illustrating stories of the glorious Tang dynasty.

Like other invaders before them, the Mongols supported the Buddhists as a matter of policy. They were particularly attracted to the esoteric and magical practices of the Tibetan Lamaists, but they also, like the Liao (遼) and the Jin (金), patronized the orthodox Buddhist sects and the Daoists. Magnificent wall paintings of about 1320 from the Xinghua Temple (興化寺), a Buddhist temple near Jishan (稷山) in southern Shanxi, are today in museums in Philadelphia, Kansas City, and Toronto, while still in situ in Shanxi and recently restored are the frescoes, dated to between 1325 and 1358, in the Yonglegong (永樂宮), a temple dedicated to the Daoist deity Lü Dongbin (呂洞賓). The Yuan also saw a large output of devotional painting, some of it done by genuine Chan monks such as Yintuoluo (因陀羅), some by professional artists such as Yan Hui (顏輝), who with his many followers painted both Buddhist and Daoist subjects in the traditional Southern Song manner.

In the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), one of the foremost figure painters was Du Jin (杜堇, fl. ca.1465-1509), who was a native of Dantu (modern Zhenjiang) in Jiangsu but spent most of his life in Beijing. He not only painted in the monochrome “baimiao (白描)” manner of delicate lines but also followed the colorful and exquisite fine-line style of the Southern Song Painting Academy figures. Du Jin’s works had a major impact on figure painting of the middle to late Ming dynasty.

Three early 16th-century professional Suzhou masters, Zhou Chen (周臣, ?-1535), Tang Yin (唐寅,1470-1523), and Qiu Ying (仇英, ca.1494-1552), established a somewhat different standard from that of the scholarly Wu group and the professional Zhe group, never renouncing the professional’s technical skills yet mastering the literary technique as well. They achieved a wide range, and sometimes a blend, of styles that could hardly be dismissed by scholarly critics. Although better known for their landscapes, their figure paintings also won great popular acclaim.

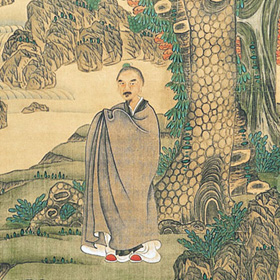

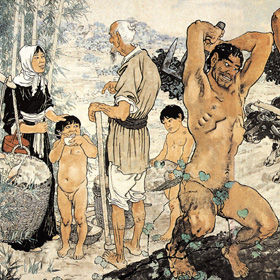

In the succeeding generations, other painting masters similarly helped confuse the distinction between amateur and professional standards, and, in the early 17th century, a number of these artists also showed the first influence of the European technique that had been brought to China through engravings and then oil paintings by Matteo Ricci (利瑪竇, 1552-1610) and other Jesuit missionaries after 1600. The southern painter Chen Hongshou (陳洪綬, 1599-1652) and the Beijing artist Cui Zizhong (崔子忠, 1574-1644) initiated the first major revival of figure painting since Song times, possibly as a result of their encounters with Western art. Perspective and shading effects appear among other naturalistic features in the art of this generation, along with a newfound interest in saturated colors and an attraction to formal distortion, which may have derived in part from a fascination with the unfamiliar in Western art. Beyond the revived interest in naturalism, which seems to have inspired in some artists a renewed attention to Five Dynasties (907–960) and Song painting (as the last period in which Chinese artists had displayed knowledge about such matters), there occurred an even more fundamental questioning of contemporary standards. In the work of Chen and Cui, which exhibits all the aforementioned qualities, an almost unprecedented interest in grotesquerie and satire visually enlivens their work, yet it also reflects something of the restless individualism and deep disillusionment that were part of the spirit of this period of national decline.

In the first half of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), figure painting in the imperial Painting Academy was heavily influenced by western techniques brought by missionaries, in particular Giuseppe Castiglione, also known as Lang Shining (郎世寧, 1688-1766). Castiglione's style was based on the emphasis on color, perspective, and light found in Italian Renaissance art. Many court painters, such as Ding Guanpeng (丁觀鵬, fl.1726-1770), drew their inspiration from Western methods of chiaroscuro and coloring as well as one-point perspective.

During the thirteen years of the Taiping Rebellion (1851-64), Shanghai had become a place of refuge for painters and rich collectors from the Jiangnan region, while the city was rapidly growing as a center of commerce. Shanghai’s newly rich patrons wanted art that was vigorous, colorful, and easy to understand. At the same time, the late decades of the nineteenth century saw a strong movement among the scholarly jinshi jia (金石家) – “metal and stone-ists,” as we might call them – to revive the ancient styles of calligraphy preserved in bronze and stone inscriptions. Together these two enthusiasms – for vigorous, colorful paintings and for calligraphy based on ancient models – came together in the work of the leading painters of the Shanghai School, or Haipai (海派), such as Zhao Zhiqian (趙之謙, 1829-84) and his follower Wu Changshuo (吳昌碩, 1844-1927), in whose paintings the somewhat emphatic form, bold color, and powerful calligraphy produce an exhilarating effect. Among Shanghai figure painters, Ren Yi (任頤, 1840-95) brilliantly brought to life again the archaistic style of the Ming master Chen Hongshou and a touch of realism that he had acquired through contact with the Western-style commercial art of Shanghai.

In the modern era, one of the most original figure painters is Fu Baoshi (傅抱石, 1904-1965). Between 1933 and 1935 Fu Baoshi studied painting in Japan, where he developed notions of a new national painting style based on a fusion of Western realism and traditional brushwork. After his return to China, Fu Baoshi taught at the National Central University in Nanjing. His landscape and figure paintings combine great delicacy of touch in the brushwork with a lyrical feeling that is lacking in the work of many of the Shanghai School.

Some other artists studied in Europe and brought back some understanding of the essential contemporary European traditions and movements. Lin Fengmian (林風眠, 1900-1991), who became director of the National Academy of Art in Hangzhou in 1928, was inspired by the experiments in color and pattern of Henri Matisse and the Fauves. Lin advocated a synthesis combining Western techniques and Chinese expressiveness and left a lasting mark on the modern Chinese use of the brush. Another major artist, Xu Beihong (徐悲鴻, 1895-1953), head of the National Central University's art department in Nanjing, eschewed European Modernist movements in favor of more conservative Parisian academic styles. He developed his facility in drawing and oils, later learning to imitate pencil and chalk with the Chinese brush. The monumental figure paintings he created would serve as a basis for Socialist Realist painters after the communist revolution of 1949.

[Based on articles from Encyclopædia Britannica, the National Palace Museum, and The Arts of China by Michael Sullivan.]