We are inviting you to our new home COMuseum.com in five seconds!

Jin Dynasty (265-420)

In early imperial times, calligraphy and painting in China were the most highly appreciated arts in court circles and were produced almost exclusively by amateurs, usually aristocrats and scholar-officials, who had the leisure time necessary to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy was thought to be the highest and purest form of painting. During the Jin Dynasty, people began to appreciate painting for its own beauty and to write about art. From this time individual artists, such as Gu Kaizhi, started to emerge. Even when these artists illustrated Confucian moral themes – such as the proper behavior of a wife to her husband or of children to their parents – they tried to make the figures graceful.

Tang Dynasty (618-907)

During the Tang Dynasty, figure painting flourished at the royal court. Artists such as Zhou Fang showed the splendor of court life in painting of emperors, palace ladies, and imperial horses. Figure painting reached the height of elegant realism in the art of the court of Southern Tang (937-975).

Most of the Tang artists outlined figures with fine black lines and used brilliant color and elaborate detail. However, one Tang artist, the master Wu Daozi, used only black ink and freely painted brushstrokes to create ink paintings that were so exciting that crowds gathered to watch him work. From his time on, ink paintings were no longer thought to be preliminary sketches or outlines to be filled in with color. Instead they were valued as finished works of art.

Beginning in the Tang Dynasty, many paintings were landscapes, often shanshui (山水, "mountain water") paintings. In these landscapes, monochromatic and sparse (a style that is collectively called shuimo-hua), the purpose was not to reproduce exactly the appearance of nature (realism) but rather to grasp an emotion or atmosphere so as to catch the "rhythm" of nature.

Song and Yuan Dynasties (960-1368)

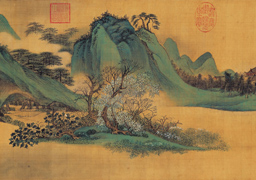

In the Song Dynasty period (960-1279), landscapes of more subtle expression appeared; immeasurable distances were conveyed through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. Emphasis was placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting and on the ability of the artist to reveal the inner harmony of man and nature, as perceived according to Taoist and Buddhist concepts. One of the most famous artists of the period was Zhang Zeduan, painter of Along the River During the Qingming Festival. Yi Yuanji achieved a high degree of realism painting animals, in particular monkeys and gibbons.

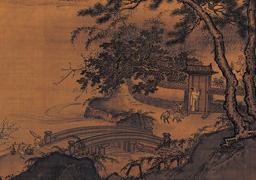

During the Southern Song period (1127-1279), court painters such as Ma Yuan and Xia Gui used strong black brushstrokes to sketch trees and rocks and pale washes to suggest misty space.

While many Chinese artists were attempting to represent three-dimensional objects and to master the illusion of space, another group of painters pursued very different goals. At the end of Northern Song period, the poet Su Shi and the scholar-officials in his circle became serious amateur painters. They created a new kind of art in which they used their skills in calligraphy (the art of beautiful writing) to make ink paintings. From their time onward, many painters strove to freely express their feelings and to capture the inner spirit of their subject instead of describing its outward appearance.

During the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), painters joined the arts of painting, poetry, and calligraphy by inscribing poems on their paintings. These three arts worked together to express the artist’s feelings more completely than one art could do alone.

Late Imperial China (1368-1911)

Beginning in the 13th century, the tradition of painting simple subjects—a branch with fruit, a few flowers, or one or two horses—developed. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than Song paintings, was immensely popular during the Ming period (1368-1644).

Some painters of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) continued the traditions of the Yuan scholar-painters. This group of painters, known as the Wu School, was led by the artist Shen Zhou. Another group of painters, known as the Zhe School, revived and transformed the styles of the Song court.

During the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), painters known as Individualists rebelled against many of the traditional rules of painting and found ways to express themselves more directly through free brushwork. In the 1700s and 1800s, great commercial cities such as Yangzhou and Shanghai became art centers where wealthy merchant-patrons encouraged artists to produce bold new works.

In the late 1800s and 1900s, Chinese painters were increasingly exposed to the Western art. Some artists who studied in Europe rejected Chinese painting; others tried to combine the best of both traditions. One of the most beloved modern painters was Qi Baishi, who began life as a poor peasant and became a great master. His best known works depict flowers and small animals.

Modern Painting

Beginning with the New Culture Movement, Chinese artists started to adopt using Western techniques. It also was during this time that oil painting was introduced to China.

In the early years of the People's Republic of China, artists were encouraged to employ socialist realism. Some Soviet Union socialist realism was imported without modification, and painters were assigned subjects and expected to mass-produce paintings. This regimen was considerably relaxed in 1953, and after the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1956-57, traditional Chinese painting experienced a significant revival. Along with these developments in professional art circles, there was a proliferation of peasant art depicting everyday life in the rural areas on wall murals and in open-air painting exhibitions.

During the Cultural Revolution, art schools were closed, and publication of art journals and major art exhibitions ceased with major destructions done as part of the elimination of Four Olds campaign.

Following the Cultural Revolution, art schools and professional organizations were reinstated. Exchanges were set up with groups of foreign artists. Chinese artists began to experiment with new subjects and techniques in their attempt to bring Chinese painting to a new height.